Implementing convolutions with stride_tricks

For an assignment on convolutional neural

networks for deep learning practical, I needed to implement somewhat efficient convolutions. I learned about

numpy.stride_tricks and numpy.einsum in the process and wanted to share it!

- Part 1 is an introduction to the problem and how I used

numpy.lib.stride_tricks.as_strided. - Part 2 is about

numpy.einsum.

Introduction

The assignment was to classify handwritten characters using convolutional neural networks. For pedagogical reasons, I needed to implement convolutions.

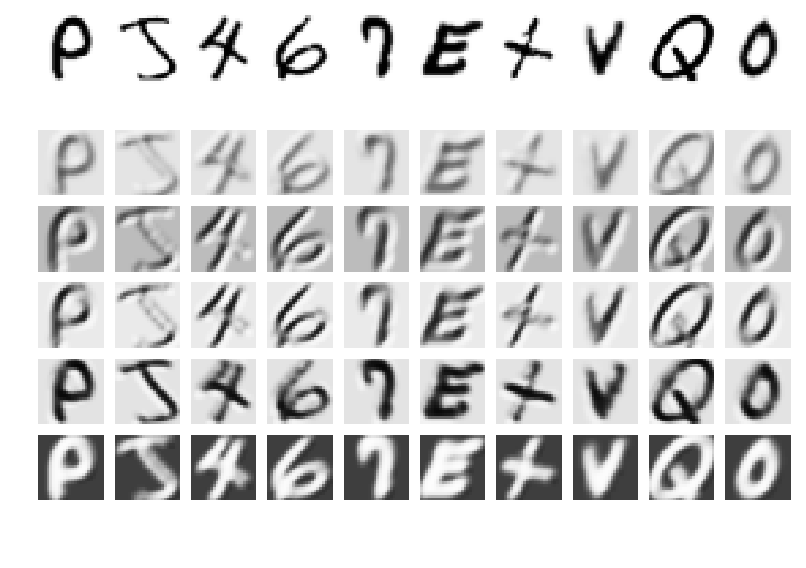

We used the EMNIST dataset. Below is a sample of 40 example images from the dataset.

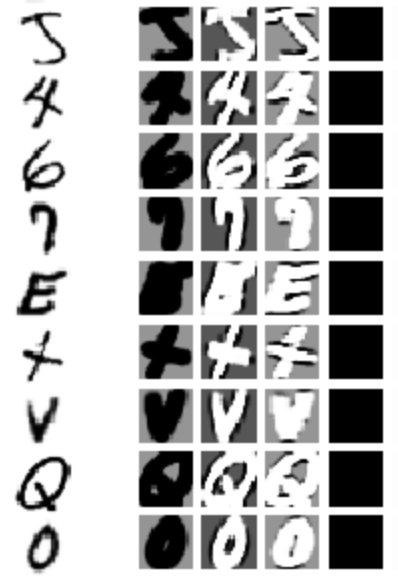

The image below shows what happens when kernels are applied (convolved). The first row shows examples. The five bottom rows are the results of convolving each of five kernels, also known as the feature maps.

Convolutional neural nets are pretty cool, but that’s all I’ll say about convolutional neural networks for now. For more information, check out cs231n.

Convolutions

The code I’m going to do in this series basically does the following (fyi: if you saw this earlier, I’ve edited it):

feature_map = np.zeros(

inputs.shape[0] - kernel.shape[0] + 1,

inputs.shape[1] - kernel.shape[1] + 1,

)

for x in range(inputs.shape[0] - kernel.shape[0] + 1):

for y in range(inputs.shape[1] - kernel.shape[1] + 1):

for i in range(kernel.shape[0]):

for j in range(kernel.shape[1]):

feature_map[x][y] += inputs[x + i][y + j] * kernel[i][j]There are a couple details on how kernels and inputs are flipped or padded (convolutions vs cross-correlations; forward propagation vs back propagation; dealing with edges), but I’ll assume inputs and kernel are already set up.

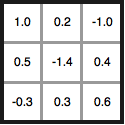

Kernels

Kernels have parameters describing how to weight each pixel. For example, below is a 3 x 3 kernel with 9 parameters:

If my input was a 3 x 3 grayscale image, I could think of putting this kernel on top of the image and multiplying each kernel parameter by the corresponding input pixel value. The resulting feature map would be a single pixel containing the sum of all pixels.

For a larger image, convolutions are done by sliding the kernel over the image to create the feature map. Here’s the canonical image:

Victor Powell’s post helped me understand image kernels.

Stride tricks

A tricky part is telling numpy to slide the kernel across the inputs.

One approach could be using the nested for-loops above, and classmates did have luck using for-loops with Numba.

I wanted to see if I could do it with numpy and came across as_strided.

as_strided tricks numpy into looking at the array data in memory in a new way.

To use as_strided in convolutions, I used as_strided to add two more dimensions the size of the kernel.

I also reduced the first two dimensions so that they were the size of the resulting feature map. To use as_strided

two additional arguments are needed: the shape of the resulting array and the strides to use.

(An aside, these high-dimensional matrices is called a tensor, as in TensorFlow.)

Shape

The way I think of this particular 4D tensor is a spreadsheet where each cell contains a little kernel-sized spreadsheet. If I looked at one cell of the outer spreadsheet, the kernel-sized spreadsheet should be the values that I multiply and sum with the kernel parameters to get the corresponding value in the feature map.

Or, in an image

By getting it into this form, I can use other functions to multiply and sum across dimensions.

Strides

One way to understand it is to imagine how a computer might store a 2D array in memory.

For a program to represent a 2D array, it fakes it. In the gif below, the left shows the faked array and the right shows an imagined memory representation. Moving left and right moves left or right, but moving up or down has to jump forward by the width.

This is where .strides comes in handy. For example, when the array goes to print the next element

to the right, I can tell it to jump forward as if it was moving down. If I do this correctly, I can

produce the results above. That said, figuring out the strides parameter is one of the trickiest parts.

Code

Phew. Here’s some example code that does this:

import numpy as np

from numpy.lib.stride_tricks import as_strided

input = np.arange(144).reshape(12, 12)

kernel = np.arange(9).reshape(3, 3)

expanded_input = as_strided(

input,

shape=(

input.shape[0] - kernel.shape[0] + 1, # The feature map is a few pixels smaller than the input

input.shape[1] - kernel.shape[1] + 1,

kernel.shape[0],

kernel.shape[1],

),

strides=(

input.strides[0],

input.strides[1],

input.strides[0], # When we move one step in the 3rd dimension, we should move one step in the original data too

input.strides[1],

),

writeable=False, # totally use this to avoid writing to memory in weird places

)Next time, I’ll show how to use this to compute the feature map.

Final note: “This function has to be used with extreme care”

As the as_strided documentation says, “This function has to be used with extreme care”.

I felt fine experimenting with it, because the code was not for production, and I had an idea of memory layouts. But I still messed up and it was interesting.

After implementing convolutions, I decided to use as_strided to broadcast the bias term. However I forgot to update a variable, and it expanded a tiny test array into a much-too-large matrix. That resulted in it pulling garbage numbers out of other parts of memory! It would randomly add things like (10^300) to my convolutions!

One thing I’m learning in machine learning is that when things are horribly broken, they can still seem to work but with a tiny bit lower performance than expected. This was one of those cases.

I didn’t realize something bad was happening and thought it was just that CNN’s are harder to train. I ended up getting it to train with a sigmoid non-linearity, with okay but not great performance.

For fun, here’s what the filters looked like:

See Also

- Part 2 is about

numpy.einsum. - Code for the class I’m in

- EMNIST: Cohen, G., Afshar, S., Tapson, J., & van Schaik, A. (2017). EMNIST: an extension of MNIST to handwritten letters. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1702.05373

- More about CNNs: cs231n

- Cool demo of kernels