Implementing Belief Propagation in Python

As part of reviewing the ML concepts I learned last year, I implemented the sum-product message passing, or belief propagation, that we learned in our probabilistic modeling course.

Belief propagation (or sum-product message passing) is a method that can do inference on probabilistic graphical models. I’ll focus on the algorithm that can perform exact inference on tree-like factor graphs.

This post assumes knowledge of probabilistic graphical models (perhaps through the Coursera course) and maybe have heard of belief propagation. I’ll freely use terms such as “factor graph” and “exact inference.”

Belief Propagation

Belief propagation, or sum-product message passing, is an algorithm for efficiently applying the sum rules and product rules of probability to compute different distributions. For example, if a discrete probability distribution \( p(h_1, v_1, h_2, v_2) \) can be factorized as

I could compute marginals, for example, \( p(v_1) \), by multiplying the terms and summing over the other variables.

With marginals, one can compute distributions such as \( p(v_1) \) and \( p(v_1, v_2) \), which means that one can also compute terms like \( p(v_2 \mid v_1) \). Belief propagation provides an efficient method for computing these marginals.

This version will only work on discrete distributions. I’ll code it with directed graphical models in mind, though it should also work with undirected models with few changes.

import numpy as np

from collections import namedtuplePart 1: (Digression) Representing probability distributions as numpy arrays

The sum-product message passing involves representing, summing, and multiplying discrete distributions. I think it’s pretty fun to try to implement this with numpy arrays; I gained more intuition about probability distributions and numpy.

A discrete conditional distribution \( p(v_1 \mid h_1) \) can be represented as an array with two axes, such as

| \( h_1 \) = a | \( h_1 \) = b | \( h_1 \) = c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| \( v_1 \) = 0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| \( v_1 \) = 1 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

Using an axis for each variable can generalize to more variables. For example, the 5-variable \( p(h_5 \mid h_4, h_3, h_2, h_1) \) could be represented by an array with five axes.

It’s useful to label axes with variable names. I’ll do this in my favorite way, a little namedtuple! (It’s kind of like a janky version of the NamedTensor.)

LabeledArray = namedtuple('LabeledArray', [

'array',

'axes_labels',

])

def name_to_axis_mapping(labeled_array):

return {

name: axis

for axis, name in enumerate(labeled_array.axes_labels)

}

def other_axes_from_labeled_axes(labeled_array, axis_label):

# returns the indexes of the axes that are not axis label

return tuple(

axis

for axis, name in enumerate(labeled_array.axes_labels)

if name != axis_label

)Checking that a numpy array is a valid discrete distribution

It’s easy to accidentally swap axes when creating numpy arrays representing distributions. I’ll also write code to verify they are valid distributions.

To check that a multidimensional array is a joint distribution, the entire array should sum to one.

To check that a 2D array is a conditional distribution, when all of the right-hand-side variables have been assigned, such as \( p(v_1 \mid h_1 = a) \), the resulting vector represents a distribution. The vector should have the length of the number of states of \( v_1 \) and should sum to one. Computing this in numpy involves summing along the axis corresponding to the \( v_1 \) variable.

To generalize conditional distribution arrays to the multi-dimensional example, again, when all of the right-hand-side variables have been assigned, such as \( p(h_5 \mid h_4=a, h_3=b, h_2=a, h_1=a) \), the resulting vector represents a distribution. The vector should have a length which is the number of states of \( h_1 \) and should sum to one.

def is_conditional_prob(labeled_array, var_name):

'''

labeled_array (LabeledArray)

variable (str): name of variable, i.e. 'a' in p(a|b)

'''

return np.all(np.isclose(np.sum(

labeled_array.array,

axis=name_to_axis_mapping(labeled_array)[var_name]

), 1.0))

def is_joint_prob(labeled_array):

return np.all(np.isclose(np.sum(labeled_array.array), 1.0))p_v1_given_h1 = LabeledArray(np.array([[0.4, 0.8, 0.9], [0.6, 0.2, 0.1]]), ['v1', 'h1'])

p_h1 = LabeledArray(np.array([0.6, 0.3, 0.1]), ['h1'])

p_v1_given_many = LabeledArray(np.array(

[[[0.9, 0.2], [0.3, 0.2]],

[[0.1, 0.8], [0.7, 0.8]]]

), ['v1', 'h1', 'h2'])

assert is_conditional_prob(p_v1_given_h1, 'v1')

assert not is_joint_prob(p_v1_given_h1)

assert is_conditional_prob(p_h1, 'h1')

assert is_joint_prob(p_h1)

assert is_conditional_prob(p_v1_given_many, 'v1')

assert not is_joint_prob(p_v1_given_many)Multiplying distributions

In belief propagation, I also need to compute the product of distributions, such as \( p(h_2 \mid h_1)p(h_1) \).

In this case, I’ll only need to multiply a multidimensional array by a 1D array and occasionally a scalar. The way I ended up implementing this was to align the axis of the 1D array with its corresponding axis from the other distribution. Then I tile the 1D array to be the size of \( p(h_2 \mid h_1) \). This gives me the joint distribution \( p(h_1, h_2) \).

def tile_to_shape_along_axis(arr, target_shape, target_axis):

# get a list of all axes

raw_axes = list(range(len(target_shape)))

tile_dimensions = [target_shape[a] for a in raw_axes if a != target_axis]

if len(arr.shape) == 0:

# If given a scalar, also tile it in the target dimension (so it's a bunch of 1s)

tile_dimensions += [target_shape[target_axis]]

elif len(arr.shape) == 1:

# If given an array, it should be the same shape as the target axis

assert arr.shape[0] == target_shape[target_axis]

tile_dimensions += [1]

else:

raise NotImplementedError()

tiled = np.tile(arr, tile_dimensions)

# Tiling only adds prefix axes, so rotate this one back into place

shifted_axes = raw_axes[:target_axis] + [raw_axes[-1]] + raw_axes[target_axis:-1]

transposed = np.transpose(tiled, shifted_axes)

# Double-check this code tiled it to the correct shape

assert transposed.shape == target_shape

return transposed

def tile_to_other_dist_along_axis_name(tiling_labeled_array, target_array):

assert len(tiling_labeled_array.axes_labels) == 1

target_axis_label = tiling_labeled_array.axes_labels[0]

return LabeledArray(

tile_to_shape_along_axis(

tiling_labeled_array.array,

target_array.array.shape,

name_to_axis_mapping(target_array)[target_axis_label]

),

axes_labels=target_array.axes_labels

)tiled_p_h1 = tile_to_other_dist_along_axis_name(p_h1, p_v1_given_h1)

# Check that the product is a joint distribution (p(v1, h1))

assert np.isclose(np.sum(p_v1_given_h1.array * tiled_p_h1.array), 1.0)Part 2: Factor Graphs

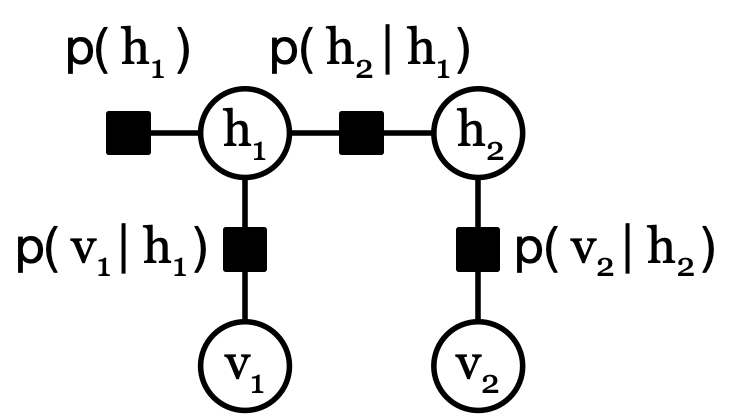

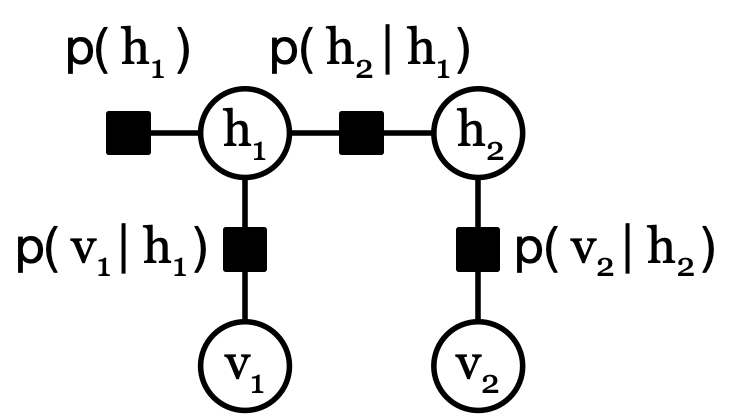

Factor graphs are used to represent a distribution for sum-product message passing. One factor graph that represents \( p(h_1, h_2, v_1, v_2) \) is

Factors, such as \( p(h_1) \), are represented by black squares and represent a factor (or function, such as a probability distribution.) Variables, such as \( h_1 \), are represented by white circles. Variables only neighbor factors, and factors only neighbor variables.

In code,

- There are two classes in the graph: Variable and Factor. Both classes have a string representing the name and a list of neighbors.

- A Variable can only have Factors in its list of neighbors. A Factor can only have Variables.

- To represent the probability distribution, Factors also have a field for data.

class Node(object):

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.neighbors = []

def __repr__(self):

return "{classname}({name}, [{neighbors}])".format(

classname=type(self).__name__,

name=self.name,

neighbors=', '.join([n.name for n in self.neighbors])

)

def is_valid_neighbor(self, neighbor):

raise NotImplemented()

def add_neighbor(self, neighbor):

assert self.is_valid_neighbor(neighbor)

self.neighbors.append(neighbor)

class Variable(Node):

def is_valid_neighbor(self, factor):

return isinstance(factor, Factor) # Variables can only neighbor Factors

class Factor(Node):

def is_valid_neighbor(self, variable):

return isinstance(variable, Variable) # Factors can only neighbor Variables

def __init__(self, name):

super(Factor, self).__init__(name)

self.data = NonePart 3: Parsing distributions into graphs

Defining a graph can be a little verbose. I can hack together a parser for probability distributions that can interpret a string like p(h1)p(h2∣h1)p(v1∣h1)p(v2∣h2) as a factor graph for me.

(This is pretty fragile and not user-friendly. For example, be sure to use | character rather than the indistinguishable ∣ character!)

ParsedTerm = namedtuple('ParsedTerm', [

'term',

'var_name',

'given',

])

def _parse_term(term):

# Given a term like (a|b,c), returns a list of variables

# and conditioned-on variables

assert term[0] == '(' and term[-1] == ')'

term_variables = term[1:-1]

# Handle conditionals

if '|' in term_variables:

var, given = term_variables.split('|')

given = given.split(',')

else:

var = term_variables

given = []

return var, given

def _parse_model_string_into_terms(model_string):

return [

ParsedTerm('p' + term, *_parse_term(term))

for term in model_string.split('p')

if term

]

def parse_model_into_variables_and_factors(model_string):

# Takes in a model_string such as p(h1)p(h2∣h1)p(v1∣h1)p(v2∣h2) and returns a

# dictionary of variable names to variables and a list of factors.

# Split model_string into ParsedTerms

parsed_terms = _parse_model_string_into_terms(model_string)

# First, extract all of the variables from the model_string (h1, h2, v1, v2).

# These each will be a new Variable that are referenced from Factors below.

variables = {}

for parsed_term in parsed_terms:

# if the variable name wasn't seen yet, add it to the variables dict

if parsed_term.var_name not in variables:

variables[parsed_term.var_name] = Variable(parsed_term.var_name)

# Now extract factors from the model. Each term (e.g. "p(v1|h1)") corresponds to

# a factor.

# Then find all variables in this term ("v1", "h1") and add the corresponding Variables

# as neighbors to the new Factor, and this Factor to the Variables' neighbors.

factors = []

for parsed_term in parsed_terms:

# This factor will be neighbors with all "variables" (left-hand side variables) and given variables

new_factor = Factor(parsed_term.term)

all_var_names = [parsed_term.var_name] + parsed_term.given

for var_name in all_var_names:

new_factor.add_neighbor(variables[var_name])

variables[var_name].add_neighbor(new_factor)

factors.append(new_factor)

return factors, variablesparse_model_into_variables_and_factors("p(h1)p(h2|h1)p(v1|h1)p(v2|h2)")([Factor(p(h1), [h1]),

Factor(p(h2|h1), [h2, h1]),

Factor(p(v1|h1), [v1, h1]),

Factor(p(v2|h2), [v2, h2])],

{'h1': Variable(h1, [p(h1), p(h2|h1), p(v1|h1)]),

'h2': Variable(h2, [p(h2|h1), p(v2|h2)]),

'v1': Variable(v1, [p(v1|h1)]),

'v2': Variable(v2, [p(v2|h2)])})

Part 4: Adding distributions to the graph

Before I can run the algorithm, I need to associate LabeledArrays with each Factor. At this point, I’ll create a class to hold onto the Variables and Factors.

While I’m here, I can do a few checks to make sure the provided data matches the graph.

class PGM(object):

def __init__(self, factors, variables):

self._factors = factors

self._variables = variables

@classmethod

def from_string(cls, model_string):

factors, variables = parse_model_into_variables_and_factors(model_string)

return PGM(factors, variables)

def set_data(self, data):

# Keep track of variable dimensions to check for shape mistakes

var_dims = {}

for factor in self._factors:

factor_data = data[factor.name]

if set(factor_data.axes_labels) != set(v.name for v in factor.neighbors):

missing_axes = set(v.name for v in factor.neighbors) - set(data[factor.name].axes_labels)

raise ValueError("data[{}] is missing axes: {}".format(factor.name, missing_axes))

for var_name, dim in zip(factor_data.axes_labels, factor_data.array.shape):

if var_name not in var_dims:

var_dims[var_name] = dim

if var_dims[var_name] != dim:

raise ValueError("data[{}] axes is wrong size, {}. Expected {}".format(factor.name, dim, var_dims[var_name]))

factor.data = data[factor.name]

def variable_from_name(self, var_name):

return self._variables[var_name]I can now try to add distributions to a graph.

p_h1 = LabeledArray(np.array([[0.2], [0.8]]), ['h1'])

p_h2_given_h1 = LabeledArray(np.array([[0.5, 0.2], [0.5, 0.8]]), ['h2', 'h1'])

p_v1_given_h1 = LabeledArray(np.array([[0.6, 0.1], [0.4, 0.9]]), ['v1', 'h1'])

p_v2_given_h2 = LabeledArray(p_v1_given_h1.array, ['v2', 'h2'])

assert is_joint_prob(p_h1)

assert is_conditional_prob(p_h2_given_h1, 'h2')

assert is_conditional_prob(p_v1_given_h1, 'v1')

assert is_conditional_prob(p_v2_given_h2, 'v2')pgm = PGM.from_string("p(h1)p(h2|h1)p(v1|h1)p(v2|h2)")

pgm.set_data({

"p(h1)": p_h1,

"p(h2|h1)": p_h2_given_h1,

"p(v1|h1)": p_v1_given_h1,

"p(v2|h2)": p_v2_given_h2,

})Part 5: Belief Propagation

We made it! Now we can implement sum-product message passing.

Sum-product message passing will compute values (“messages”) for every edge in the factor graph.

The algorithm will compute a message from the Factor \( f \) to the Variable \( x \), notated as \( \mu_{f \to x}(x) \). It will also compute the value from Variable \( x \) to the Factor \( f \), \( \mu_{x \to f}(x) \). As is common in graph algorithms, these are defined recursively.

(I’m using the equations as given in Barber p84.)

Variable-to-Factor Message

The variable-to-factor message is given by:

where \( ne(x) \) are the neighbors of \( x \).

def _variable_to_factor_messages(variable, factor):

# Take the product over all incoming factors into this variable except the variable

incoming_messages = [

_factor_to_variable_message(neighbor_factor, variable)

for neighbor_factor in variable.neighbors

if neighbor_factor.name != factor.name

]

# If there are no incoming messages, this is 1

return np.prod(incoming_messages, axis=0)Factor-to-Variable Message

The variable-to-factor message is given by

In the case of probabilities, \( \phi_f(\chi_f) \) is the probability distribution associated with the factor, and \( \sum_{\chi_f \setminus x} \) sums over all variables except \( x \).

def _factor_to_variable_messages(factor, variable):

# Compute the product

factor_dist = np.copy(factor.data.array)

for neighbor_variable in factor.neighbors:

if neighbor_variable.name == variable.name:

continue

incoming_message = variable_to_factor_messages(neighbor_variable, factor)

factor_dist *= tile_to_other_dist_along_axis_name(

LabeledArray(incoming_message, [neighbor_variable.name]),

factor.data

).array

# Sum over the axes that aren't `variable`

other_axes = other_axes_from_labeled_axes(factor.data, variable.name)

return np.squeeze(np.sum(factor_dist, axis=other_axes))Marginal

The marginal of a variable \( x \) is given by

def marginal(variable):

# p(variable) is proportional to the product of incoming messages to variable.

unnorm_p = np.prod([

self.factor_to_variable_message(neighbor_factor, variable)

for neighbor_factor in variable.neighbors

], axis=0)

# At this point, we can normalize this distribution

return unnorm_p/np.sum(unnorm_p)Adding to PGM

A source of message passing’s efficiency is that messages from one computation can be reused by other computations. I’ll create an object to store Messages.

class Messages(object):

def __init__(self):

self.messages = {}

def _variable_to_factor_messages(self, variable, factor):

# Take the product over all incoming factors into this variable except the variable

incoming_messages = [

self.factor_to_variable_message(neighbor_factor, variable)

for neighbor_factor in variable.neighbors

if neighbor_factor.name != factor.name

]

# If there are no incoming messages, this is 1

return np.prod(incoming_messages, axis=0)

def _factor_to_variable_messages(self, factor, variable):

# Compute the product

factor_dist = np.copy(factor.data.array)

for neighbor_variable in factor.neighbors:

if neighbor_variable.name == variable.name:

continue

incoming_message = self.variable_to_factor_messages(neighbor_variable, factor)

factor_dist *= tile_to_other_dist_along_axis_name(

LabeledArray(incoming_message, [neighbor_variable.name]),

factor.data

).array

# Sum over the axes that aren't `variable`

other_axes = other_axes_from_labeled_axes(factor.data, variable.name)

return np.squeeze(np.sum(factor_dist, axis=other_axes))

def marginal(self, variable):

# p(variable) is proportional to the product of incoming messages to variable.

unnorm_p = np.prod([

self.factor_to_variable_message(neighbor_factor, variable)

for neighbor_factor in variable.neighbors

], axis=0)

# At this point, we can normalize this distribution

return unnorm_p/np.sum(unnorm_p)

def variable_to_factor_messages(self, variable, factor):

message_name = (variable.name, factor.name)

if message_name not in self.messages:

self.messages[message_name] = self._variable_to_factor_messages(variable, factor)

return self.messages[message_name]

def factor_to_variable_message(self, factor, variable):

message_name = (factor.name, variable.name)

if message_name not in self.messages:

self.messages[message_name] = self._factor_to_variable_messages(factor, variable)

return self.messages[message_name] pgm = PGM.from_string("p(h1)p(h2|h1)p(v1|h1)p(v2|h2)")

pgm.set_data({

"p(h1)": p_h1,

"p(h2|h1)": p_h2_given_h1,

"p(v1|h1)": p_v1_given_h1,

"p(v2|h2)": p_v2_given_h2,

})

m = Messages()

m.marginal(pgm.variable_from_name('v2'))array([0.23, 0.77])

m.messages{('p(h1)', 'h1'): array([0.2, 0.8]),

('v1', 'p(v1|h1)'): 1.0,

('p(v1|h1)', 'h1'): array([1., 1.]),

('h1', 'p(h2|h1)'): array([0.2, 0.8]),

('p(h2|h1)', 'h2'): array([0.26, 0.74]),

('h2', 'p(v2|h2)'): array([0.26, 0.74]),

('p(v2|h2)', 'v2'): array([0.23, 0.77])}

m.marginal(pgm.variable_from_name('v1'))array([0.2, 0.8])

Example from book

Example 5.1 on p79 of Barber has a numerical example. I can make sure I get the same values ([0.5746, 0.318 , 0.1074]).

pgm = PGM.from_string("p(x5|x4)p(x4|x3)p(x3|x2)p(x2|x1)p(x1)")

p_x5_given_x4 = LabeledArray(np.array([[0.7, 0.5, 0], [0.3, 0.3, 0.5], [0, 0.2, 0.5]]), ['x5', 'x4'])

assert is_conditional_prob(p_x5_given_x4, 'x5')

p_x4_given_x3 = LabeledArray(p_x5_given_x4.array, ['x4', 'x3'])

p_x3_given_x2 = LabeledArray(p_x5_given_x4.array, ['x3', 'x2'])

p_x2_given_x1 = LabeledArray(p_x5_given_x4.array, ['x2', 'x1'])

p_x1 = LabeledArray(np.array([1, 0, 0]), ['x1'])

pgm.set_data({

"p(x5|x4)": p_x5_given_x4,

"p(x4|x3)": p_x4_given_x3,

"p(x3|x2)": p_x3_given_x2,

"p(x2|x1)": p_x2_given_x1,

"p(x1)": p_x1,

})

Messages().marginal(pgm.variable_from_name('x5'))