Master's thesis on convolutional encoders in seq2seq neural lemmatization

This summer I wrote a thesis for my AI masters! As part of my end-of-the-year clean up, I wanted to post about it. In addition to this post summarizing my thesis, I posted about encoder-decoder seq2seq and using max-pooling.

Thesis

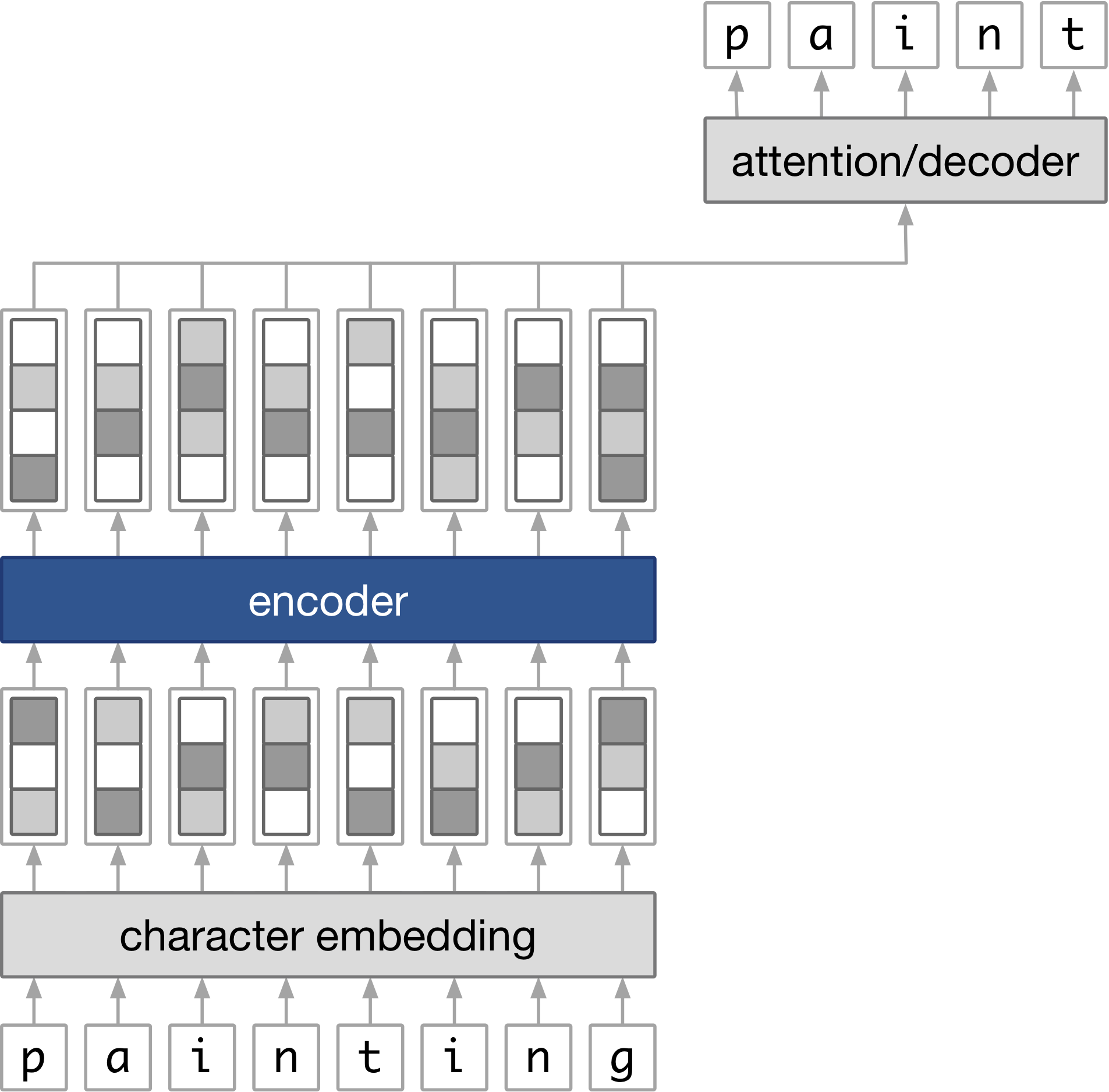

Starting with an encoder-decoder sequence-to-sequence neural network that can lemmatize in several languages, I replaced the encoder component with convolutional layers and measured how well it could still lemmatize.

This post includes the motivation for neural lemmatizers and trying convolutional encoders.

Neural Lemmatizers

A lemmatizer converts a word to its lemma. The lemma is the form that would appear in a dictionary. For example, in “I am running”, running is the surface form of the lemma run.

Some other words-lemma pairs are

| word | lemma |

|---|---|

| painted | paint |

| running | run |

| changed | change |

| occurred | occur |

| caught | catch |

| generations | generation |

| treehouses | treehouse |

Lemmatization can be a useful preprocessing step in natural language processing. If I’m coding a search engine to find posts about the search term “vacation”, I might want to return articles that mention either “vacation” or “vacations.” To merge these words, I could use a lemmatizer as a preprocessing step.

(Another way to do text normalization is stemming. I differentiate lemmatizing and stemming in this project by saying that lemmatizing produces the form of the word that would appear in a dictionary, while stemming doesn’t necessarily produce a real word.)

Three approaches for lemmatization

To motivate neural lemmatization, I think it helps to start with how I would build a lemmatizer from scratch.

The lemmatizer in my formulation takes in a string, such as “running”, and returns another string, in this case “run”. This is why it is considered a sequence-to-sequence problem: the lemmatizer takes in a sequence of characters and returns a second sequence of characters.

In Python, the function would look like:

def lemmatize(word : str) -> str:

...

return lemmaOne way to implement lemmatize is to build a dictionary that maps words to their lemmas.

word_to_lemma = {

'painted': 'paint',

'running': 'run',

}Then to lemmatize, I’d just need to look up the word in the dictionary:

def lemmatize(word):

return word_to_lemma[word]The dictionary approach could probably get me far. However, one issue is that the dictionary would need to be updated to handle out-of-vocabulary words like new words, such as “podcasting,” or domain-specific words, such as “andesites.” Another issue is that the dictionary may get very large for some languages. For example, Finnish has 62 conjugations for the word ‘to read’!

A second approach could be encoding lemmatization rules. The rule “remove the suffix ‘ing’” could lemmatize “climbing,” “painting,” and “cooking,” as well as the out-of-vocabulary word “podcasting.” And conveniently, as you may already know if you’ve studied a second language, rules for converting a lemma to its inflection are already written down for many languages in grammar books.

Back in Python, I could start writing something like:

def lemmatize(word):

if word.endswith('ing'):

lemma = word.replace('ing', '')

# Remove repeating final letter (e.g. in 'occurring')

if lemma[-1] == lemma[-2]:

lemma = lemma[:-1]

...

return lemmaA third approach, and the one I explore in my thesis, is automatically learning the lemmatization function from a list of words and their lemmas. The list of words and their lemmas could be a longer list version of the one from above:

| inflection | lemma |

|---|---|

| painted | paint |

| running | run |

| changed | change |

| occurred | occur |

| caught | catch |

| generations | generation |

| treehouses | treehouse |

One way to learn to map a string to another string is using seq2seq neural networks, which have already performed well in another NLP transduction task, neural machine translation.

Aside: Do I really need to automatically learn rules?

In most languages, the inflection rules are already known, so automatically learning lemmatization not discovering anything new. And if by chance a language needs lemmatization rules, we only need to learn the rules once. Having lemmatizer that can learn how to lemmatize any language is a little overkill.

I had a few reasons, but my favorite is that because lemmatization can be done by learning rules, the seq2seq can be viewed as reverse-engineering those rules from their input and output. Being able to automatically reverse-engineer rules is really neat! If it works well, maybe it could also be applied to other string transformation functions or regular expression replacements.

Convolutional encoders in Lematus

An existing neural lemmatizer is Lematus. Lematus is based on the open-source neural machine translation framework Nematus.

Lematus is an encoder-decoder neural network with attention. The focus of my thesis was swapping out the encoder component for different configurations of convolutional layers, and measuring if it could still accurately lemmatize.

Recurrent Encoder

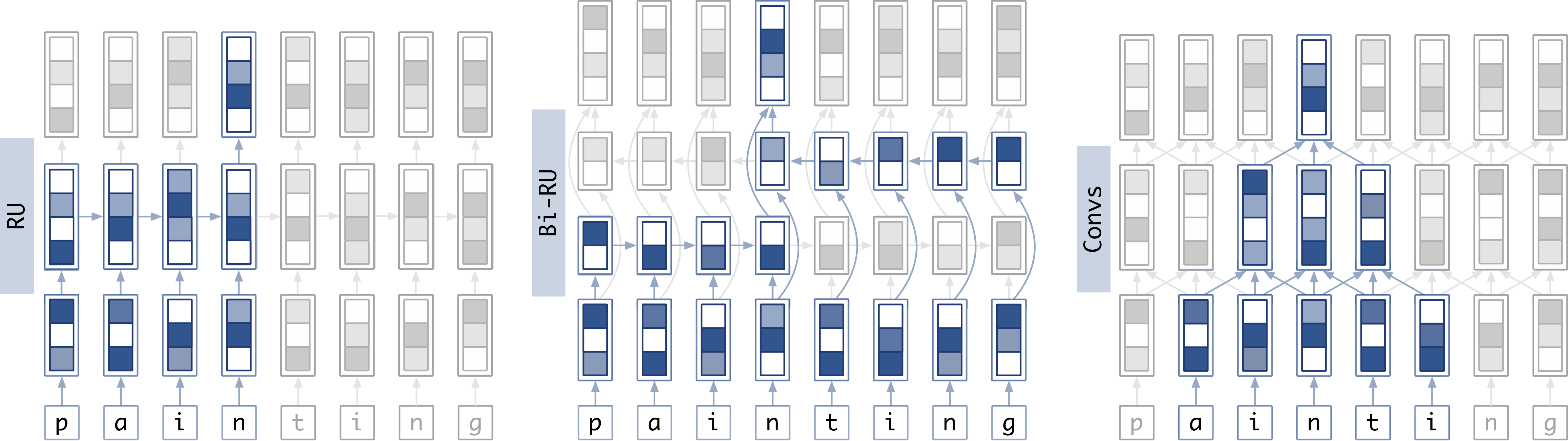

At a high level, I can compare how data flows through different types of components.

The above shows a comparison of how data flows through a recurrent unit, a bidirectional recurrent component, and two convolutional layers. Vectors are represented by the rectangles containing colored squares. In all cases, the sequence of characters (bottom row) is first passed through an embedding layer that results in a sequence of vectors (length-3 vectors in the second-from-bottom row). Regardless of if recurrent units or convolutional layers are used, the output of the components is another sequence of vectors of the same length as the input sequence (represented by the top row of length-4 vectors.) Arrows represent what data is combined to form the next vector. The highlighted boxes show how data traveled from the input sequence to a given element of the output sequence.

Recurrent unit (left) shows the flow of information of a uni-directional recurrent unit (one row of length-2 vectors, representing the hidden state size 2).

Bidirectional recurrent component (center) shows the flow of information of a bidirectional recurrent unit (two rows of length-2 vectors, again representing a hidden state size 2.) The highlighted vectors show how each output timestep of the sequence is influenced by the entire input sequence.

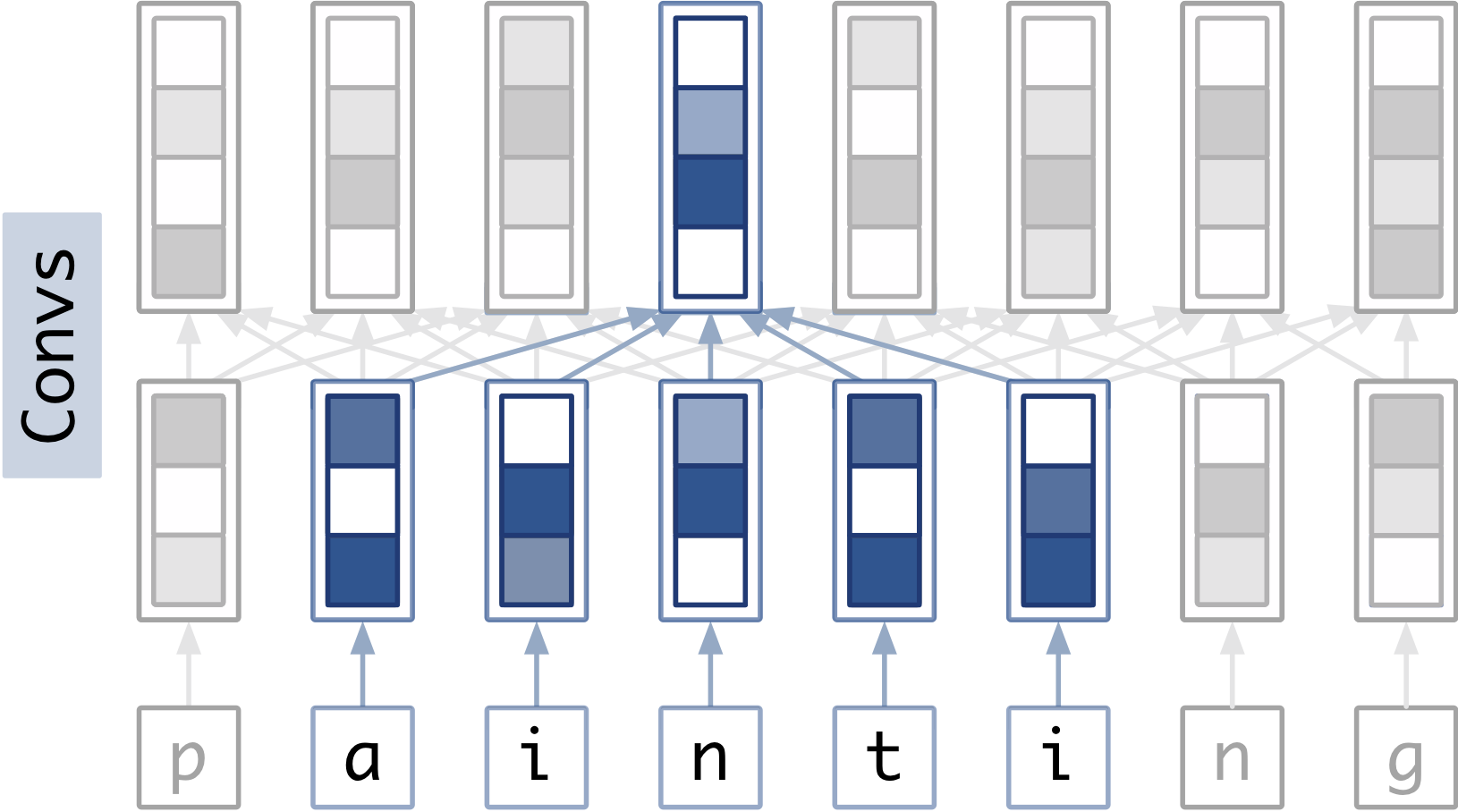

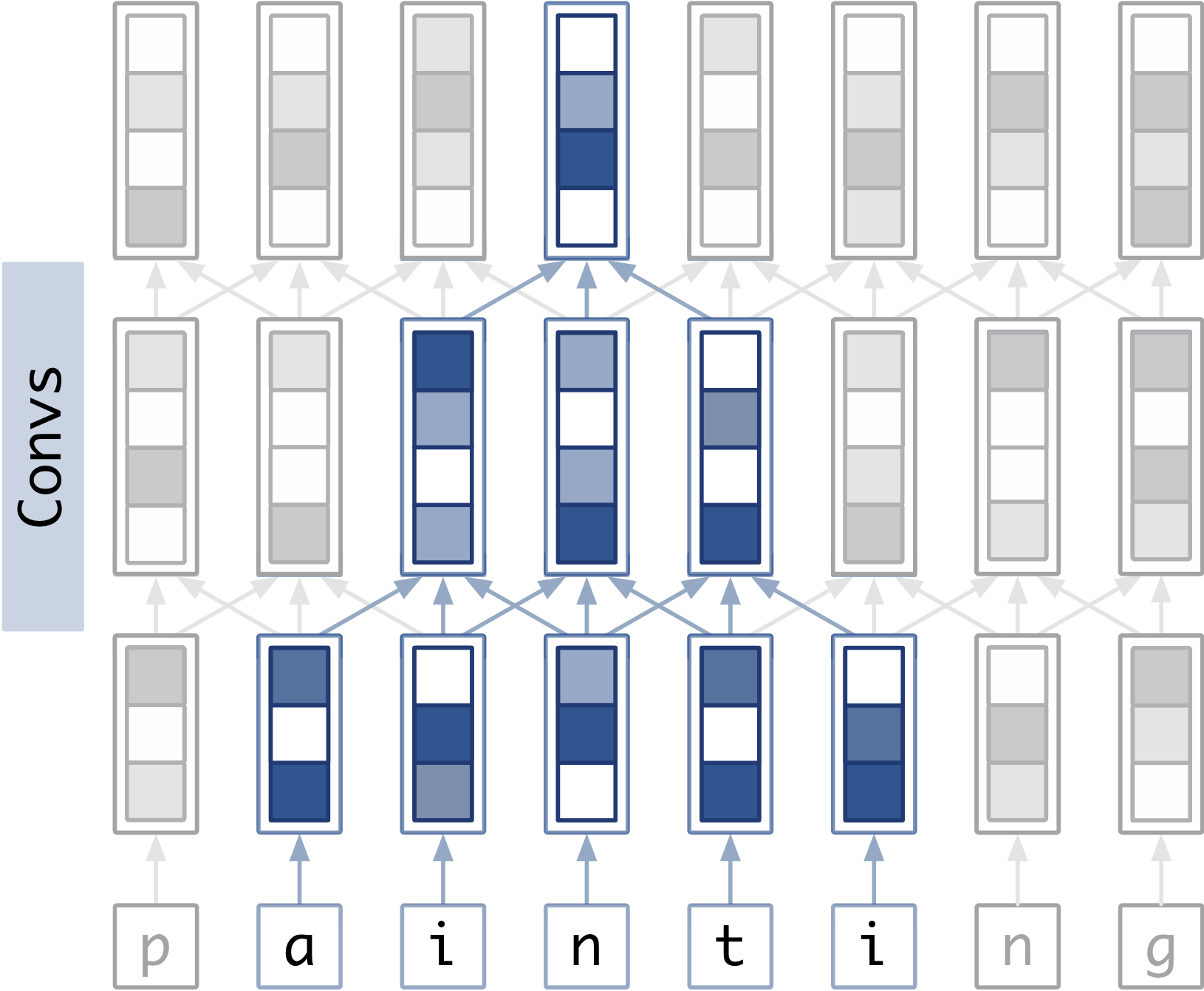

Convolutional layers (right) shows the flow of information through two convolutional layers with kernel size = 3 (the first layer is the set of arrows connecting the embedded sequence to the intermediate representation of length-4 vectors, and the second layer is the set of arrows connecting the intermediate representation to the output sequence.)

Depth vs receptive field

Since using a convolutional layer in place of the bidirectional recurrent component would reduce the receptive field size, I was curious how important the receptive field was. I first varied the size of the receptive field by changing the convolution’s kernel size.

Another idea is that deeper networks can learn hierarchical things. Otherwise, deeper networks might just perform better because they use data from a larger area. I tried to compare the performance of deeper convolutional encoders with shallower ones with the same receptive field.

|

|

Findings

The findings were that

- Only for some languages did the convolutional encoders perform as well as the recurrent ones. The accuracy of the architectures with convolutional encoders maxed out, which was sometimes lower than the recurrent encoders.

- Different languages reached their maximum performance at different convolution kernel sizes.

- Convolutional layers sped it up.

Other things

- A fun part of this project that I didn’t get to write about in the thesis was building software to help me manage all of my experiments, which I wrote about here instead.

- Five years ago, I wrote a program that does morphological inflection in Haskell to help me learn rules for Swedish!

- As my MSc was at Edinburgh, it was called a dissertation!